Last year, Plymouth State University was the partial recipient

of a grant from the National Science Foundation to integrate research across state

lines. As a result, LoVoTECS expanded its network into coastal Maine in order to investigate water quality

related to closure of beaches and shellfish flats (http://www.newenglandsustainabilityconsortium.org/safe-beaches-shellfish).

We are excited to welcome our new partners,

who include: the Hancock & Cumberland County Soil and Water Conservation

Districts, City of Ellsworth, Kennebec Esutary Land Trust, UMaine Cooperative Extension/Tanglewood 4-H Camp,

Coastal Studies for Girls and the Town of Hampton!

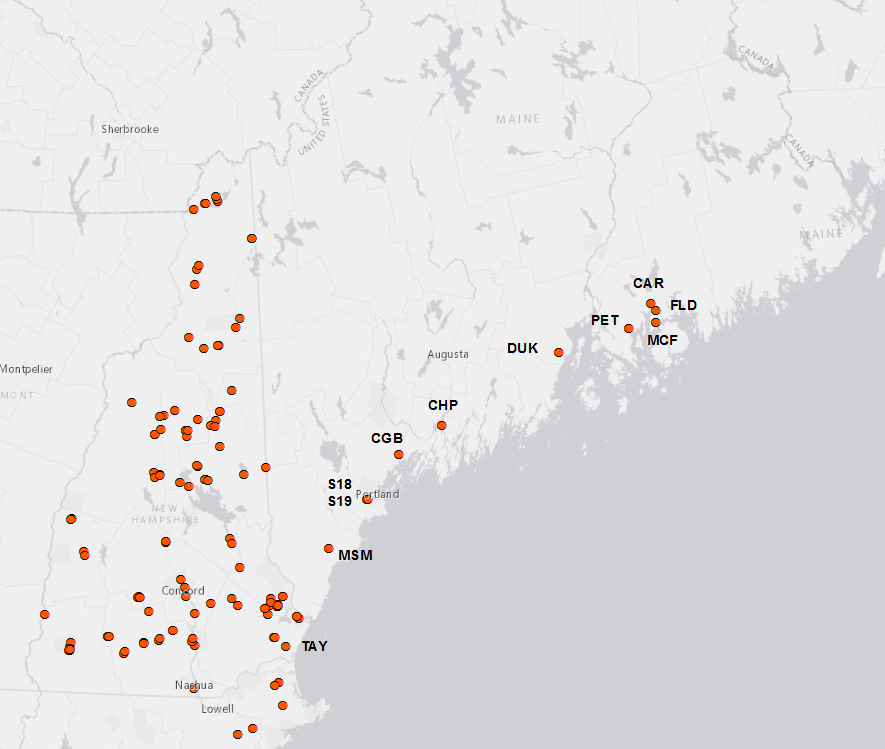

Below is a list of the new sites installed this field season:

1. Mousam River, Kennebunk, ME (MSM)

2. Card Brook, Ellsworth, ME (CAR)

3. McFarland Brook, Trenton, ME (MCF)

4. Flood Steam, Surry, ME (FLD)

5. Peters Brook, E. Blue Hill, ME (PET)

6. Long Creek, Portland, ME (2 sites: S18, S19)

7. Concord Gully, Freeport, ME (CGB)

8. Merrymeeting Bay/Chopps Point, Woolwich , ME (CHP)

9. Ducktrap River, Lincolnville, ME (DUK)

10. Taylor River, Hampton, NH (TAY)

Our data will help provide information for other interests

besides beach and shellfish closures- Check out the restoration project at Long

Creek site: http://www.restorelongcreek.org/

.JPG)